Song of a New Goddess

“…Beneath the centuries of enquiry and renunciation, beneath the effort to settle what trembles at the root of perception, a current persists in which speech does not chase meaning but moves within its wake. It cannot be recovered by discipline; it enters when holding releases. Older than thought, older even than prayer, it stirs as syllable meeting silence with the delicacy of flame taken to wick. In that flicker, before there is light, there is presence—the quiver of the Goddess, resting in her own resonance, allowing the scene to dissolve even as she inclines toward utterance again…”

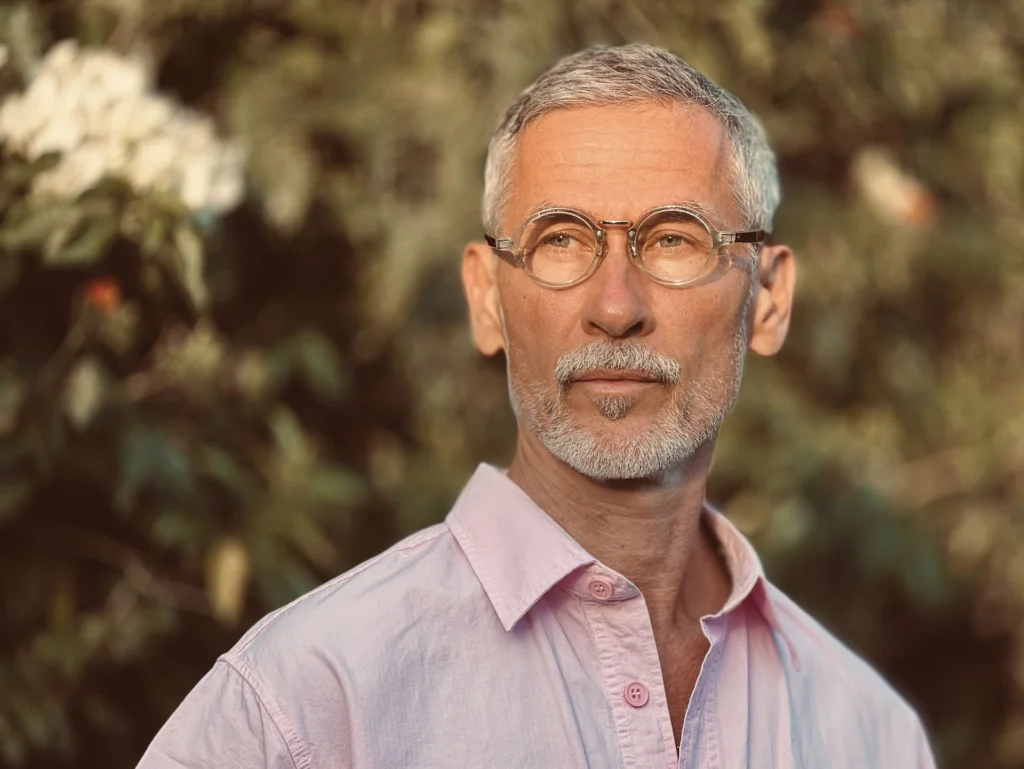

~ Igor Kufayev

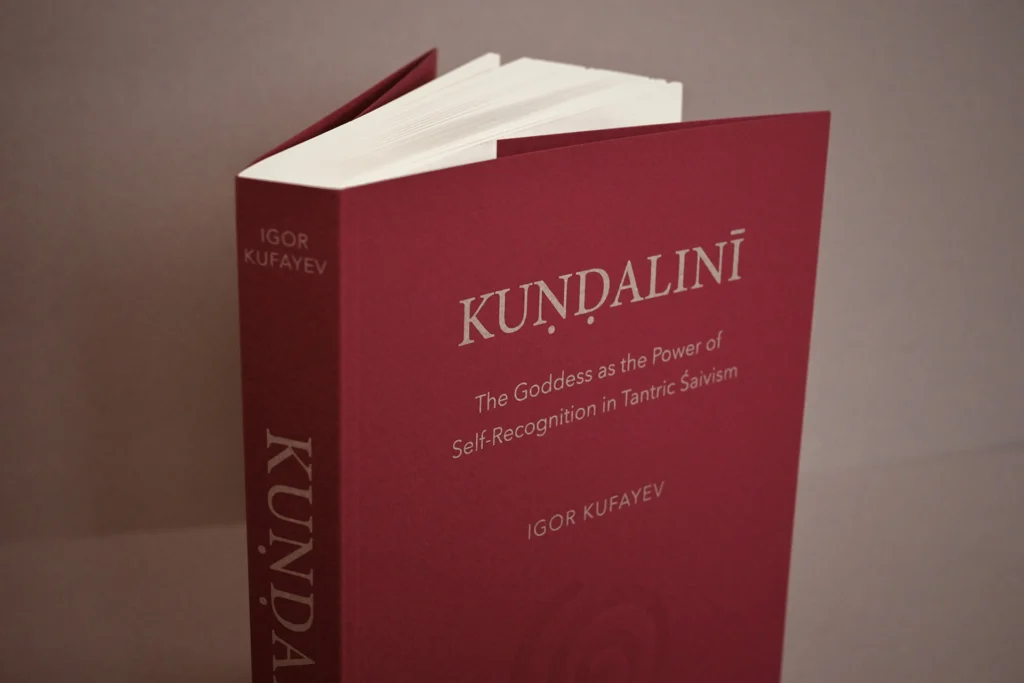

We honour, in deepest adoration, this special day of January 5th, 2026, to commemorate and celebrate the birthday of our beloved Teacher, Igor Vamadeva Kufayev, together with the publication of his second book, KUṆḌALINĪ: The Goddess as the Power of Self-Recognition in Tantric Śaivism—a work that gathers and gives form to decades of transmission and lived experience.

Rebirth to a New Consciousness

Seen in the light of that which weaves occasion with its meaning, this milestone perhaps reflects a certain conscious coherence as it arises with the 60th year of our teacher. In Vedic tradition, it is known as Shastipurti, a time of great transition, considered a rebirth in its own right. It marks that conscious shift from fulfilling the obligations of worldly life to one dedicated in service of Spirit. Yet what does such a transition signify for one in whom the Self stands realised, where the cycle of birth and death is transcended?

Perhaps, for one fully tuned to the state of Unity, this ritual moment is no longer a mere metaphor but is lived as a continuous cosmic act—in and through which the rebirth of a new consciousness is being spoken forth into the world.

The Movement of this Work

For many years, we have grappled with the paradoxical difficulty of putting into words the immensity of this work and how it impresses itself upon anyone who has experienced it firsthand, or even sensed it through proximity. The undeniable transformation it brings defies description. Speech itself becomes suspended in the face of such experience, rendering futile any attempt to surface what has truly taken place.

Even more elusive is the recurring phenomenon—the samavesha-kriyas—those harmonies that reverberate in the space of each immersion, pouring themselves out through each individuality as an utterly involuntary yet entirely natural response to what is being touched.

What happens in this work is at once the most natural and the most supernatural in its movement. All we know with certainty is that something seeks to be brought into the world—bearing the voice of something as awe-inspiring and terrifying as the physical act of birth itself, with its deepest contractions and outermost expansions.

Commemoration of Life

And perhaps for the first time—as if to time itself to the measure of infinity—a hint has been given to what truly takes place in the room each time those who feel called gather in the name of the One. As though the sheer desire to honour rather than seek description lays bare the fundamentally life-giving nature of this process. Which in turn is what enables us to fully sound and partake in all the notes of the glory of existence, not merely in outlook but in every step of the path leading us home.

All glory to the masters who have allowed the light of this path to unfold. All glory to the midwives of consciousness, attending the continual rebirthing of the One and Only. May this light shine into the world at its darkest hour, received through the cracks in every heart, revealing and fulfilling what this work holds and has been consecrated to accomplish.

The following reflections are taken directly from the published KUṆḌALINĪ book itself and are offered here as a hymn of entrance into the heart of the teaching and the governing Power of this work. They come as close as language can manage to convey the essence of it all… an Ode to Life itself…

Song of a New Goddess

by Igor Kufayev

Sanātana Dharma is unlike most inherited ways of being human in one decisive respect: it has no founder, no originating prophet, no single revelation anchoring its authority. It is uncreated in the way a river is uncreated—gathering itself from springs seen and unseen, shaped by centuries of vision, ritual, contemplation and the quiet labour of remembrance. What draws me is not the notion of a fixed doctrine but the sense of an unbroken rapport: a millennia-long communion-in-sound between the human and the divine, carried across hymns in a gesture of the highest offering, philosophical treatises and grandmother-songs murmured at dusk. Vedic seers, epic poets, nobles in a true measure of that status, tantric adepts, householders, all pouring water to the rising sun—answering, each in their own accent, the same primordial question: how does one honour this astonishing fact of being alive at all?

At what point in this long thread did the tone of that conversation begin to change? When did the hymns to the radiant powers of the Goddess in the Ṛg Veda—where reality greeted as vast, untameable and life-bestowing—start to give way to a very different mode: the insistence that life is, at its root, suffering? When did the emphasis shift from praising the splendour of manifestation to seeking an exit from it? Or perhaps there have always been two parallel currents: one that sings repeatedly of a bond that must be renewed through recitation and offering, and another that arises out of sheer exhaustion with the human condition and turns toward release?

The figure of the Buddha stands exactly at this fault line. We do not know what ‘the’ teaching of the Buddha was; already in his lifetime there existed dozens of schools, and what we call ‘Buddhism’ today is a whole continent of differing visions. Yet they share a common ground in the recognition of duḥkha—as the first of the Four Noble Truths, and as a key to interpreting the entire field of experience. Existence, as embodied and conditioned, is unsatisfactory. This is not a small claim. It is a lens that reinterprets every joy as fragile, every pleasure as suspect, every bond as shadowed by ending.

And with the Buddha, something else entered the bloodstream of civilisation: a mass culture of seeking. How many today realise that with him the quest for liberation stepped out of the forests and hermitages and into the centre of human aspiration? That what had long existed in the Vedic and Śramaṇa worlds, with mokṣa as a goal and renunciation as a path, suddenly took on a new, almost universal urgency? One has to wonder how many of today’s seekers still carry, knowingly or not, that very inheritance: the blessing and the burden of striving for release, even to the extent of locating freedom in the extinguishing of desire at its root, as nirvāṇa came to be understood. With the Buddha the question of suffering became not just a philosophical concern but a civilisational imperative, a call that reshaped the spiritual aspiration of Asia for millennia.

There is a long and formidable history of questioning this vision. The classical challenge—from Śaṅkara in the south to Abhinavagupta in the north—was not casual dissent but a philosophical objection of considerable force: if there is no enduring self (anattā), what is it that attains the final release? If the skandhas are transient and consciousness is contingent, who or what arrives at the unconditioned? And if nirvāṇa is nothing but cessation—of craving, of becoming, of the aggregates themselves—does liberation not risk collapsing into a refined form of annihilation? Buddhist masters, of course, pushed back against the charge of nihilism with great subtlety, insisting that nirvāṇa lies beyond the binaries of existence and non-existence. Yet from the outside, the question remains unavoidably sharp: what are we being asked to relinquish—and into what, precisely, do we disappear?

It is not my intention here to adjudicate these debates. I am not interested in scoring points in an ancient contest of metaphysics. What concerns me is something simpler, more existential: where does the road fork between a worldview that sees embodied life fundamentally as a burden to be transcended, and one that sees embodiment as the very theatre of the Divine? That is the question that continues to press on me—personally, philosophically, spiritually.

No wonder Kuṇḍalinī is dismissed (or denied) in mainstream Buddhism. Outside the esoteric currents of Vajrayāna, there is little in the canonical landscape that could make sense of Her movements. Even today one can witness the bewilderment in Western Zen halls and Theravāda centres when this power stirs in a practitioner: the sudden surges of heat, the involuntary trembling, the unbidden expansions of awareness. I have met students, some of whom were ordained zen monks, whose teachers—highly respected rōshis and rinpoches, trained for decades in pristine settings—were left standing on the shore, uncertain of what tide had risen in their own saṅgha. The old zen manuals do not speak of this, not in a way that one can apply it in concrete clinical conditions anyway. What arrives is treated as an ‘unwanted display’, something to be stabilised, contained or meditated away. All of which sounds easier said than done.

From the standpoint of those traditions, their caution makes perfect sense. The early discourses of the Buddha do not articulate a notion comparable to Kuṇḍalinī; the path is framed in terms of mindfulness, ethical restraint and the dissolution of craving, not the awakening of a latent śakti. In the Pāli Nikāyas, the striking energetic phenomena that can accompany deep absorption are noted only to be set aside as distractions. Even in the great Mahāyāna systems, Chan, Zen and Pure Land, the emphasis rests on mental clarity, compassion and the direct perception of emptiness, not the unfolding of an embodied current of grace. What encouragement could there be, in such a framework, for acknowledging a force that moves through the body like fire through a fuse?

Historically, this emphasis did not arise in a vacuum. It was also a response: to ossified ritual, to the brahminical monopolising of the sacred, to structures that reduced the divine to a hereditary privilege. The Buddha’s uncompromising stand lay partly in severing that monopoly, insisting that direct insight is not the birthright of a class but the capacity of consciousness itself. Yet somewhere along this trajectory, a certain disenchantment with incarnation seems to have hardened. To speak in very broad strokes, much of the Buddhist inheritance comes to be read through the aspiration of ‘cutting’ the cycle of saṃsāra once and for all, to bring the traffic of birth and death to a halt.

In truth, this question did not remain theoretical for long. One need only look at the contours of this life to see why the Buddha’s first noble truth once felt like an unassailable axiom. On paper, given the biography of this body, I should be entirely aligned with that reading. There has been no lack of duḥkha. I lived through the collapse of the world into which I was born, witnessing the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the unraveling of everything once deemed certain. I had to make my way forward in a culture whose language I did not speak, whose codes I did not understand. And in my mid twenties, I carried the loss of my six-year-old daughter in an accident that tore through every remaining seam of coherence. Loss, illness, breakdown, the very real derangement that accompanies the tearing open of the psyche—none of this was foreign terrain. For a time, the Buddha’s diagnosis seemed almost self-evident: of course this entire arrangement is riddled with suffering. Of course any joy here is short-lived, precarious, already shadowed by its own ending.

Artists, by virtue of the acuity of their perception, learn early that whatever life delivers must be worked with through the act of creation. No matter how glorious or shattering, the artist’s task is to metabolise experience and return it as an offering—so that wholeness may be sensed even through the isolated fragment all true works of art inevitably are. Often not by preference but by necessity: experience demands to be transmuted, given form, made bearable through the shaping of an image, a line, a gesture. In that sense, the true artist is a meditator in disguise; perhaps not seated in stillness, yet submitting reality to the discipline of attention and allowing the process to draw one closer to essence.

For years, this was the only way I knew how to remain in dialogue with existence. Art held what the psyche could not. And then came the moment when even that alchemy could no longer contain the voltage. What had once served as reckoning through pigment and canvas began to demand another vessel. In my years as a painter, the challenge was never merely to refine a style or extend the boundaries of a chosen medium. The true work was to widen the aperture of perception until the image could bear something of what pressed inward from a place prior to thought. I was not drawn to the ‘sense of irony’ or the conceptual meanderings dominating much of the contemporary, and predominantly corporate art scene—where the artwork becomes commentary on art itself. For me, painting was never about the game of reference. It remained a devotional act, even if I would not have used that word at the time.

The canvas became a field of transmutation, not of ideas but of forces. Gesture, pigment, texture—these were not elements to be arranged but conduits, allowing what was sensed inwardly to cross the threshold into form. Each stroke carried the attempt, however imperfect, to breathe something of the ineffable into visible matter. I had always believed, instinctively, that the vitality of a work of art lies in whether that current survives the passage through the hand. And for a time, that was enough. Until it was not. There came a point when the medium itself—however merciful, however refined—could no longer contain what was seeking articulation. The pressure was no longer satisfied by colour and structure. What had once taken shape through canvas and hand-made paper began to ask for a more porous vessel, one not confined to a rectangle, a tondo or an ellipse on a stretcher. At that threshold, going inward did not appear as a departure from art, but as its continuation by subtler means. If salvation could be found through art alone, I would have been in the highest heaven by my late twenties. But it could not. That is when meditation offered itself as an act of grace in more ways than I can recall here.

Almost instantly, I found myself re-rooted—quite literally—in all orientations and aspirations, toward heaven. Not because suffering had ceased or become more bearable, but because something in its very fabric revealed itself as indispensable: chosen, deliberate, luminous. The world did not stop wounding; it simply ceased to appear devoid of meaning. Or, perhaps more accurately, meaning and life blended into a single impulse—the sheer fact of being alive. Beneath the surface turbulence, beauty redefined itself: the axis shifted from an objective sphere of experiences to an ever-deepening recognition of the subject as the locus from which perception arises. What appeared ‘out there’ felt increasingly like a continuation of one’s own subterranean, insistent, unmistakably real interior.

It is in this light that the later polemics of Indian thought begin to interest me—not as academic disputes, but as tremors in this deeper question. Śaṅkara, in the eighth century, and Abhinavagupta, two centuries later, both engaged Buddhism with a sharpness that cannot be dismissed as mere sectarian rivalry. Śaṅkara regularly accuses certain Buddhist schools of falling into nihilism, of erasing the reality of the Self behind an abstract śūnyatā. Abhinavagupta, from within the Trika Śaiva vision, criticises doctrines of momentariness and radical non-self on the grounds that they cannot account for the continuity of awareness, nor for the palpable fulness (pūrṇatā) in which the world actually appears. Both, in their own ways, are defending a life-affirming metaphysics against what they perceive as a drift toward existential anemia.

I do not bring this up to take sides in a historical debate. I am not a historian of religions; I leave that labour, with all respect, to those who are called to it. What interests me is not who was ‘right’ in some final sense, but the divergence of attitude they reveal. At one pole, a vision in which the highest good lies in finally extinguishing the compulsion to incarnate, in stepping off the wheel for good. At the other, a vision in which manifestation is recognised as the very sport of the Absolute, a real shimmering of Śiva’s own body, to be seen through, yes, but not dismissed as an error.

This book has been written from the second vantage point. Not out of naivety around suffering, but out of intimacy with the force that moves through suffering and gives it contour. I am not arguing a thesis here. I am simply speaking from where I stand: as someone who has known the pit and the pinnacle, who has watched the nervous system torn open and rewoven, who has accompanied others through the long night of their own undoing. From here, the core question is no longer abstract. It is brutally simple: does our spirituality deepen our capacity to be here, or does it secretly collude with our aversion to life?

Seen in that light, the rehabilitation of Kuṇḍalinī is not a side-topic, and not an indulgence for the esoterically inclined. It goes to the heart of the civilisational story. If the power that shapes and maintains this embodied existence is cast as an obstacle to be overcome or a delusion to be exposed, then the body, the senses, the world will always be suspect. If, on the other hand, Kuṇḍalinī is recognised as the Goddess—Vāc, the speaking power of Consciousness; the very principle by which the Infinite assumes form—then this life becomes the privileged site of recognition. Not a karmic trap, not some kind of rehabilitation ground, but the very medium through which Śiva remembers Himself.

The reflections that follow are written in that spirit. They are not meant as a new doctrine, nor as a settled verdict on the long and complicated history of Indian thought. They are simply my attempt to trace how this question of—nihilism and affirmation, escape and embodiment—threads its way through my own life and through the teachings that have formed me. From there we can turn, more quietly, to the vision of the Vedic seers, to their astonishing intuition that human life is not a cosmic accident but the deliberate arrangement of the Infinite for the sake of its own self-reflection. And from that vantage, the song of a new goddess can perhaps be heard for what it has always been: not a new melody, but an ancient one remembered, on a different shore.

In the vision of the Vedic seers, the human experience is not an accidental by-product of a restless universe, nor some random station on a cosmic evolutionary chart. It is the fruit of a deliberate narrowing, an artistry of incalculable subtlety, by which the Infinite arranges the conditions for its own self-reflection.

The tattvas, those thirty-six principles of manifestation, are the very blueprint of this descent. At their summit shine the śuddha-tattvas, the five pure categories, where consciousness abides as it is—Śiva–Śakti, radiant, undivided and whole. Moreover, even will, knowledge and action are not yet fractured into separate currents but remain a single pulsation, a boundless reservoir in which the entire play of existence lies unexpressed.

Yet that plenitude cannot savour itself unless it first fashions a point from which to gaze. As Abhinavagupta tells us, consciousness sees itself as other in order to experience the bliss of its own nature. To paraphrase in my own voice: manifestation is Śiva radiating as creation to behold His own magnificence through the infinite points of view.

For such a gaze to be possible, the limitless must first don the garments of limitation. This happens in the middle register of manifestation, the śuddhāśuddha-tattvas, where infinity begins to veil itself. And here, the veiling takes on a precise form: the kañcukas, the five ‘coverings’, sheaths of constrictions with Māyā Śakti at its source. These are not chains imposed by some external force; they are the conscious narrowing of an all-seeing eye so that it may fall in love with the particular.

Through kalā, omnipotence becomes the measured reach of a hand, the limited scope of an action. Through vidyā, omniscience folds into the intimacy of partial knowing—so that discovery, surprise and learning may exist. Through rāga, perfect fulness bends into longing, into the exquisite ache of desire. Through niyati, the Absolute binds itself to a here—a location in the vastness—so that there is somewhere to stand, somewhere to walk. Through kāla, the eternal takes on a now, allowing events to unfold in sequence, making the poignancy of beginnings and endings possible.

These five coverings rest within a deeper seal formed by the triad of mala–māyā–karma, by which the Infinite accepts the gravity of embodiment. Mala, in its threefold form, dims the brilliance of self-recognition, like a film drawn across a mirror, so that the gaze falters in recalling its own vastness. Māyā, the great measurer, casts infinity into partitions, carving the many from the One so that each form may glimmer in distinction. Karma threads every act to its echo, binding gesture to consequence, weaving the continuity of a life. Together they press the boundless into a single vantage, veiled enough for the light to pass through, yet firm enough to seal itself into the human condition as the narrow gate through which the Infinite peers into its own becoming.

Existence is no fall from perfection, but a movement within perfection. Śakti, stirred by longing, lets her wail soften, and dissolve into song. What begins as a cry is transfigured into resonance, a tone that ceaselessly carries itself through the vast ocean of sound. In that shimmering expanse, her voice becomes the utterance of Śiva’s name—syllable upon syllable, vibration upon vibration—until the whole fabric of existence is nothing other than a shimmering ocean of sound. And so creation itself is born, the very voice of the Beloved sounding through every fibre of being.

This wailing is present in the agony of every separation down here where manifestation touches the Earth. It echoes through the chambers of all its levels, through every fracture in this world. It rises in the heartbreak of lovers parted, in the silence that falls when friendship turns to ash, in the bellowing of the calf torn from the side of its mother. It resounds when the mind pulls away from the heart, when brothers and cousins raise their hands against each other, when nations fracture into war. The same cry quivers through all these rifts, as though every wound carries the echo of that primordial severing.

Yet the song remains the same, for the Goddess transformed the pain of separation into a most intimate, innermost, anthem of return. What begins as lament becomes the undercurrent of longing that binds the world together. It moves not only through the human heart but through the very body of creation: in the splitting of stars, in the breaking of seasons, in the tectonic shifts of the earth as it reshapes itself. Even in the ebb and surge of the tides, there is this pulsing ache, this ceaseless rhythm of parting and reunion.

For those whose hearts are tuned to its melody, the cry is not mistaken for despair. They hear in it the hidden vow of return, the secret promise already woven into the sorrow. To walk in that song is to walk as healing itself, to carry in one’s presence the very touch that soothes the rift, the embrace that mends the fracture. And thus, through each who awakens to its cadence, the anthem of return resounds more clearly, gathering the scattered fibres of creation back into the voice of the Beloved.

It does not end at the edge of the heart or the borders of the body. It moves outward, seeping into the field between us, filling the silence of night, threading itself into the cadence of rain, dwelling in the rustle of leaves stirred by winds no one sees. It stretches across the interval between every gathering and every parting, saturating the very air with its resonance.

When one leans deeply enough into this song, there is no longer a need to hold the world together—because leaning deeply enough means becoming one with the world. Held in the trembling of that one note, carried in the endless breath of the Goddess. It is the vibration that steadies the heart, the rhythm that underlies the seasons, the hum that sustains the stars in their turning. The song is the binding. The resonance is the bond. And as it lengthens into stillness, it is no longer clear where the wail ends and the song prevails, where grief dissolves into joy, or longing into arrival. Only resonance remains, unbroken, unending, un-struck sound as the most tangible expression of silence. And in that silence, the Goddess waits, holding within Her breath the power to sound it all again.

In the embodied state, we rarely perceive these as divine artistry. They are simply the conditions of our lives. We are born into a place and time, with a particular range of knowing, a hunger for what we do not yet have, and the capacity to act only within certain bounds. Yet to the adept, to the one who has traced the arc of consciousness back to its source, these are seen for what they are: the deliberate brushstrokes of the Infinite painting a scene in which the self can meet itself.

Without these constrictions, there would be no narrative, no texture, no depth of contrast. A sunset would be indistinguishable from the blaze of noon; the face of a lover would dissolve into the faceless expanse. The fragrance of Arabian jasmine at night could not move us if it were not this fragrance, here, now, in a darkness that will not last.

This narrowing is not an act of deprivation, it is the means by which the whole spectrum of experience becomes possible. The human sensory field, seemingly so narrow compared to the vast range of frequencies in existence, is not a defect. It is an intentional tuning. We cannot see into the infrared without being blinded by heat; we cannot absorb ultraviolet without being burnt into absence—thank God for that, literally. We are placed, as if in the most artfully orchestrated of gardens, exactly where the balance of forces allows for the tender perception of beauty. Between the realms that would fry us and those that would dissolve us into cold silence, here is the window where sight, sound, touch, taste and scent meet in their most luminous proportion.

This is Māyā not as deception but as divine measure—the careful calibration that permits the Infinite to appear as a world worth beholding. The Vedic seers knew this, praising the gods not for removing the veils but for weaving them so artfully that life itself becomes the unfolding of wonder—ānanda perceptible in form.

This vision is expressed through the cosmology of ābhāsa-vāda, the ‘shining forth’ of an outward projection of Śiva’s all-encompassing power to know Himself as the World. Every perception is an ābhāsa, a luminous self-appearance of consciousness. The sight of a hill’s shadow stretching at dusk, the sound of a bell from across the courtyard, the scent of rain in the air before it falls—none of these are objects ‘out there’. They are consciousness turning toward itself, appearing in a form it can feel, and savour.

The tanmātras, the subtle essences of sensory experience, are the secret templates for this self-revelation: śabda (sound), sparśa (touch), rūpa (form), rasa (taste) and gandha (smell). They are not inert building blocks but living patterns, each a distillation of a particular vibration of awareness. Every melody you have ever loved, every embrace that warmed you to your bones, every play of light on moving water begins here, in these subtle seeds. When you shout into the void, or whisper a friend by name, you are taking part in the same creative act by which Śiva calls the world into being.

To live with this understanding is to see that the apparent limits of perception are not bars but frames. A window does not imprison the view; it shapes it. The horizon does not bind the sea; it offers the form within which its vastness can be savoured.

And it is here that a line from Pink Floyd’s Breathe comes back to me, not as an anthem of confinement, but as a hymn to this divine framing: And all you touch and all you see is all your life will ever be. Heard in the ordinary way, it almost sounds as a prison-like sentence, a matter of imposed boundaries. Heard in the light of the tattvas, it speaks of the perfect placement of those boundaries, of the filters by which the Infinite has arranged for this moment to exist exactly as it does—like a perfectly tuned instrument, resonating in the register where the Goddess is poised to sing.

Before Kuṇḍalinī entered the language of yoga and tantra as the name of the awakened current, the sages spoke of Vāc—the Goddess as Word. In the earliest stratum of the tradition, she gives voice to herself. The Devī Sūkta of the Ṛg Veda (X.125) resounds in the first person:

I am the Queen, the gatherer-up of treasures,

the knower, foremost among those worthy of worship.

Through me alone all eat, all breathe, all see, all hear;

unheeding, they dwell in me.

Here, speech is no ornament draped upon a pre-existing world. It is the generative act itself, the pulse by which reality stirs into being and comes to know itself. Centuries later, the Śaiva–Tantric masters did not abandon this Vedic vision but gave it sharper contours in a metaphysics of sound. Vāc is the Goddess’s own power of manifestation, unfolding in four gradations: parā, supreme, unstruck sound; paśyantī, the first inward flash of creative vision; madhyamā, the subtle vibration of thought moving toward articulation; and vaikharī, voiced utterance audible to the ear. These are not poetic embellishments but ontological strata themselves, charting the descent of undivided awareness into the differentiated world.

Seen in this light, the supposed gap between Vāc and what later comes to be called Kuṇḍalinī nearly dissolves. In Śākta sources and in Kashmiri doctrine alike, the Word is the latent power coiled at the the womb of creation: parā at rest in silent Śakti, as Kuṇḍalinī lays dormant in a respective chamber. As that current awakens, speech itself unfolds with each gradation, from paśyantī, to madhyamā, to vaikharī the cosmos comes forth, for the world is nothing if not articulated revelation. This is the phonic physiology traced by Abhinavagupta, clarified by Padoux, and before him systematised in the classic syntheses of Sir John Woodroffe in The Garland of Letters and The Serpent Power.

The imagery is exacting. The Goddess bears a garland of letters, varṇamālā for the Sanskrit alphabet is her body; the circle of Mātṛkās, the Mothers of sound, is her wheel. Mālinī, the presiding Śakti of the Mālinīvijayottara Tantra so central to Abhinavagupta, means ‘She of the Garland’. All worlds are strung upon that mala of phonemes. Beings are bound by these same Mothers when their source is forgotten, and liberated by them when the current turns inward and the letters are tasted as conscious light.

Placed here, at the close of a work on Kuṇḍalinī, the older name clarifies the newer: before she rose as Serpent, she sang as Word. Awakening is not merely a surge of heat along the spine or a current flashing in the skull; it is the remembrance of Vāc—the recognition that perception itself is phonic, that every sight, touch and thought is but a syllable in the Divine uttering itself into being. When the current ascends through the suṣumṇā, it is also speech retracing its steps toward source: vaikharī softens into madhyamā, thins into paśyantī and comes to rest in the plenitude of parā. Breath becomes utterance (uccāra), and utterance becomes the silent tremor of Being itself.

If Vāc is the utterance of the world, then rasa is its relish. One brings forth, the other lingers. Between them there is no fracture, what the Goddess speaks, she also tastes. For the masters of Kashmir Śaivism, the aesthetic and the spiritual are not parallel pursuits but a single current: consciousness delighting in its own resonance.

Abhinavagupta calls rasa the ‘soul of poetry and drama’, yet in his Abhinavabhāratī—commentary on Nātyaśāstra, an ancient treatise on dramaturgy—he makes it plain that it is also the soul of life. Every experience, entered without resistance, contains a flavour, an essence that, once freed from the sediment of self-reference, becomes universal. The grief of one heart can open into the grief of all beings; a fleeting joy at a child’s laughter can widen into the joy of the cosmos beholding itself.

This is not to be confused with the gusts of bhāva-samādhi found in devotional currents: the sobbing, trembling or sudden ecstasies that can break upon the body like weather. They have their place and beauty, but they are still capricious like weather. Rasa is what remains when the sky clears: the distilled essence of emotion, luminous and steady, transparent enough to reveal the source from which it flows. For the Trika adepts, this is the highest aesthetic relish and the most intimate spiritual sentiment: the savour of consciousness tasting itself through the medium of emotion.

At the summit, and beneath it all, stands śānta-rasa—the flavour of peace. This is no pallid detachment but the radiant quiet that holds all other flavours in completion. Love (śṛṅgāra), courage (vīra), wonder (adbhuta), compassion (karuṇā), humour (hasya), fury (raudra), fear (bhayanaka), disgust (bibhatsa)—each, carried to its fulness, dissolves here, as rivers yield to the sea. Śānta is not the absence of colour; it is the light in which all colours are gathered, the still clarity where every taste finds its resting place.

For the one who has awakened, to re-enter the weave of the world is to move again through the play of rasa—not as one lost in its tides, but as one who drinks from them with open eyes. The very constrictions of embodiment, the kañcukas, are no longer chains but chalice: the narrow vessel in which nectar ferments. The human form, with all its limits, shows itself as a work of perfect proportion—confining just enough to grant shape, spacious enough for the Infinite to shine through.

Here, your own life, however unadorned, unspectacular, is revealed as the Goddess’s theatre of delight. In the clatter of the marketplace, in the still kitchen at night, in the chance smile of a passerby—rasa is present. The warmth of a friend’s hand, the cadence of rain on glass, the bitterness of an unripe fruit, each is a note in the great rāga of awareness. They need not be grand to be profound; they only need to be entered without turning away.

When emotion is met in this way, without grasping, without recoil, it clears itself. Tears may fall, though not into sorrow; they fall into a vastness that does not weep. Laughter may rise, though not to distract; it rises from a stillness that is not looking to be entertained. This is not detachment but intimacy without possession—the seasoned art of being fully in the world without being tightened by it. And here the circle draws near: what was first uttered as Vāc is now tasted as rasa, the Word returning as flavour. Creation speaks itself, and in its speaking becomes sweet upon the tongue of awareness.

And thus the thread moves, without seam, from Word to Taste: the Goddess who utters the world is the one who savours it. What she speaks, she tastes; what she tastes, she returns in play as līlā, shimmering with the distilled essence of the Real.

There are moments when language carries remembrance of how it came into the world. A breath rising toward what it could sense but not hold, given shape only because silence tipped into sound. Before devotion had form, before seeking acquired method, there was this: awareness leaning outward as utterance. As incantation. As the first attempt to keep pace with the motion of possibility. Eternity submitting itself to measure. The earliest hymns were shaped in that bending.

Something of that remains. Beneath the centuries of enquiry and renunciation, beneath the effort to settle what trembles at the root of perception, a current persists in which speech does not chase meaning but moves within its wake. It cannot be recovered by discipline; it enters when holding releases. Older than thought, older even than prayer, it stirs as syllable meeting silence with the delicacy of flame taken to wick. In that flicker, before there is light, there is presence—the quiver of the Goddess, resting in her own resonance, allowing the scene to dissolve even as she inclines toward utterance again.

She is there in the pause before a word takes form, in the gathering of breath that precedes articulation, in the thread across which sound travels into being. And she is there in the bloom of the word—its warmth, its hue, its savour—as much as in the echo that settles after it, the way a note lingers inside the body long after its pitch has vanished into the air. She is utterance and residue, vibration and quiet held in a single pulse.

Through her body runs the garland of letters, the varṇamālā, each syllable a turning of the universe upon itself. She moves through them as wind through ripe grain, bending each stalk to cadence, drawing forth a sound that arrives both singular and manifold. The Mothers of sound, the Mātṛkās, circle at her feet, weaving speech and thought, perception and recollection, until all of creation is tuned to her breath.

Her song carries renewal. No refrain exhausts itself, no pattern grows stale; each instant reveals itself as the first articulation. This is why her voice enters even the most familiar room with the freshness of arrival. She is the tide that smooths the traces of what passed and lays bare the sand, unmarred, without pause, without fatigue.

To rest within her voice is to feel the world sound itself as a single utterance. The wind through leaves, thunder unrolling past the ridge, porcelain meeting wood, the rise and fall of a lover’s breath—each is a modulation of the same exhalation. In that breath, time loosens its direction; it folds inward, serpent-like, drawing every moment back toward origin. Past and future unknit into the depth of the present, and what stands revealed bears no edges.

*

The above is an excerpt from the published work, KUṆḌALINĪ The Goddess as the Power of Self-Recognition in Tantric Śaivism, taken from the chapter named as ‘Reflections’. The book is available now to purchase and can be ordered at www.songpublishing.org/kundalini

Photos: Courtesy of Flowing Wakefulness.

Responses

Reading these lines feels like the words reading themself to me. A very strange yet lovely feeling as English is not my mother tongue. I can not even describe it as reading it was more like hearing a song, an intimate melody. Reading this excerpt from the Kundalini book is a blessing, thank you 🙏🏽

I’m very thankful to have a teacher like you Vamadeva, I’m bowing down in gratitude and wishing you a happy birthday 🌱

JGD 🕊️

Dear Vamadeva,

I cannot put into words what this deep knowledge opens in my heart; I am profoundly grateful to know this connection. It is truly a grace to know that here the work is lifted up like a Holy Grail, and that guidance is granted to those who behold it with longing in their hearts, as I do. Thus, it is a surrender and a turning toward that which we perceive as love and song in the heart, and which takes form here. I hold the book in my hands, and the heart merges with the words—what a grace, divinity in glory, a true taste of peace.

Jai Guru Dev and Happy Birthday 📿🤍🙏

A call answered.

Offering it all.

Guiding as the One.

Returning into the One.

Throbbing as the One.

Dearest Master,

bowing down to the fire that is yours. The alchemical flame ignited in the heart. Warming and clearing at the same time. No way to surmise what it may take to preserve and carry forth the guiding light. Oh, what an offering.

May you have the most wonderful birthday, dearest Teacher. May you always be protected. And all those dear to your heart.

In deepest gratitude,

Jai Guru Dev 🙏🏾

Dearest Teacher of the Heart,

May what I cannot express be already spoken.

Thank you for this gift, that are these words.

A most happy birthday. May you and the family have a day filled with joy and beauty.

With immense gratitude,

Jai Guru Dev

Huda

Dearest Master-ji,

Wishing you a most wonderful HAPPY BIRTHDAY!

The KUṆḌALINĪ book has just arrived, and I feel deeply grateful. I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for pouring so much of your heart and knowledge into this work for the benefit of so many.

Even reading only a few pages, I could immediately feel the energy and the transmission that flows through it — a living presence that carries your depth, clarity, and love.

Your teaching and service continue to inspire me in countless ways, and being your student is a blessing beyond words.

Enjoy your special day!

With much love

Your Shishya

Prema

Dearest Teacher,

I am still deeply grateful that our paths were allowed to cross.

A sentence, no, even a single word from you, whether spoken or written, as here, makes my heart shining bright and my awareness rise, so that I can continue tirelessly on this path of heart, there and back.

Words for my gratitude for being your student are hard for me to find. May gratitude, humility, devotion, and joy, through the vibrations that connect us all, be the unclouded and unfound words.

From the bottom of my heart, Happy Birthday! I wish you and your family a wonderful, beautyfull and unforgettable day.

Jai Guru Dev

Dearest Vamadeva,

Nine years I know you, how much my respect, my appreciation and my love to you keeps growing.

And at the same time my awareness opens further and my sense of I deepens.

I feel more infinite and focused then ever.

Thank you my dearest teacher.

May you always be showered with the greatest there is

With love

Jai Guru Dev

Jai Sri Kundalini Ma 🌹

An ode to you today, Dearest Vamadeva.

The finest vibrations of the heart awaken in your presence.

Vibrations of pure Beauty, Love, and everlasting Knowledge.

Like the Breath, golden and life-giving,

they resonate deeply through my entire being.

In immense gratitude, I bow to you, my Teacher.

Wishing you an utmost Blissful Birthday.

with love,

Jai Guru Dev

Jai Sri Kundalini Ma

Dearest Master, vessel for the Teaching to stream in clear waters never stale,

Indeed, the world does not stop wounding. Thank You for pointing to its luminous meaning, always.

From the Fulness comes the Fulness. May this birthday be the gate into a great and Gracious transition.

May the benefactors support the benefactor You are.

Bowing in gratitude ~ all glory to the Divine… 🙏🏽

Nothing makes sense if it is not

filled with the quiver

of her.

Thank you for telling the tale

of her. And embodying

her completely this

birth.

Your birth is the most

auspicious thing.

Unending waves of gratitude.

Yet not fully recognized.

As they would split me apart,

slowly, gently, fiercely.

All in remembrance of her.

My deepest gratitude for

your birth.

Dearest Vamadeva.

May there be warmth, Love, peace

for you and your loved ones. From this (yesterdays) full day onward.

Dearest Vamadeva,

With my heart resting with you

now, through the turning hours, and always,

I silently honor the sacrifices required to stand in the many roles you fulfill,

depths beyond what can ever be fully known.

I am thinking of the hundreds, near and far,

who speak your name as their Teacher, their Guide, their Beloved.

I hold your words closest, when you have alluded to how this work

may one day be asked to be carried onward.

Of all the things I wish for you, may silence be among them.

May we serve your work with the fullest measure we are capable of.

May its sacredness always be preserved.

No words can describe the tenderness,

embalmed with the taste of Love not from this world…

Bowing at your feet

Beloved Vamadeva,

Jai Guru Dev